3 August 1915

Having relieved 47 Division, 15 Division was now responsible for the right sector of IV Corps on a front 4,200 yards wide. The 13th Battalion of the Royal Scots moved up into the front trenches. Robert and his colleagues in D Company were prepared to be pitched into immediate face-to-face action against the German Army.

Loos-en-Gohelle was a typical mining village of the area. Its layout was to resemble that of the ‘garden village’ of Denbeath that Robert had so recently left behind. A count of the inhabitants of Loos-en-Gohelle in 1911 recorded a population of 4,749, with most working men employed and housed by mining companies. The vast majority of 1,875 lived in the area of La Cite No. 5, belonging to Mines de Béthune.

Attr : By kind permission of Paul Reed

(http://battlefields1418.50megs.com/loos.htm)

Numerous towns in the Lille conurbation, Douaisis and the mining basin around Lens had fallen into German hands in early October 1914. On the evening of 4 October 1914, the first shells rained down on Loos and struck the church bell tower. The closeness of the fighting prompted the first inhabitants of Loos to flee. There had been fierce fighting between the French soldiers of the 109th Infantry Regiment and German units of the 110th Baden Regiment for control of the village and its resources. Under the pressure exerted by the German army, French troops posted in Loos were forced to beat a retreat and the village was permanently occupied from 10 October 1914 onwards.

The Germans established very strong positions in the surrounding area having taken over all of the high ground. They had now had a formidable set of defences in what became known as their ‘Race to the Sea’. For example, the pit ‘bings’, or slag heaps, provided excellent reconnaissance opportunities and placements for heavy artillery. These mining waste sites complemented higher ground such as ‘Hill 70’ outside Loos.

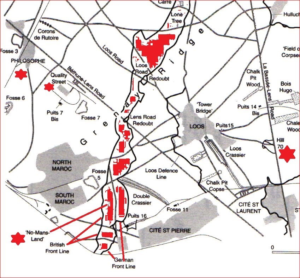

A, B and C Companies of 13th Battalion of the Royal Scots each had 1 platoon in the front trenches and their other 3 platoons in support trenches. The ‘keeps’ at Quality Street North and Quality Street East were each occupied by a platoon from D Company, who were permanently garrisoned with Battalion HQ.

The remaining two platoons of D Company, including Robert Dunsire, were in reserve at billets at Quality Street. The latter platoons operated as ‘fatigue parties’ and were responsible for taking food to the rest of the men, from the Quartermaster (QM) stores at Quality Street.

The forward platoons sent a man from the front to act as guides for the fatigue parties, so meals were delivered quickly and they did not get lost in the zig-zag communications trench network.

During this period at the front, the battalion suffered its first casualty when Corporal J. Irvine, a fellow member of Robert’s D Company, was severely wounded when his elbow was shattered by fragments of a shell. Sadly, another colleague of Robert, Private J McGhee of the Reserve Machine Gun Section in billets at Le Philosophe, was killed be a piece of shell striking him in the stomach. Another 2 men were severely wounded.

This first foray to the trenches sadly ended with a number of casualties: on 14 August, the War Diary records that 2 casualties had died of wounds, 1 killed accidentally and 8 ranks wounded. There were no officer deaths. However, World War I witnessed the death of many officers as they led from the front: 17 per cent of officers were killed during World War I.

The battalion was relieved when they moved back 3 miles west to the mining village of Noeux-les-Mines, on 18 August. On arrival at Noeux the list of casualties had grown: 2 killed, 9 wounded, 20 evacuated sick out of divisional area, and 2 officers and 11 men in hospital. The evacuation routines were already well tested and the Royal Army Medical Corps had a slick process of triage to ensure casualties were directed to the correct level of care behind the lines with hospitals established on the Channel coast.

Robert and the battalion were not allowed to put their feet up when they moved back from the positions at or very close to the Front. For instance, little instruction in bombing had been possible back in England due, probably, to a lack of material in sufficient quantities to meet the requirements of the forces in France and those training at home. Instruction was also necessary in the tactical handling of machine guns. Although looked upon as quiet, the sector was subject to constant shelling. Every night, working parties of 400 men were involved in trench-maintenance fatigues.

Bombing classes were held at the divisional school in Noeux-les-Mines.

The preparations for battle continued as each platoon in each company trained its four sections, in: wiring; bombing; machine-gun use; and mining. Meanwhile, officers were trained to be expert in at least two of these subjects. Robert Dunsire was a machine-gunner.

After two weeks of further training the battalion returned to familiar territory at the billets at Le Philosophe, as part of 45 Brigade Reserve from 31August. There was some ordinariness to life: 2nd Lieutenant James was taken to hospital with appendicitis. Working Parties of 400 men returned to trench duties in the reserve and communications trenches, as trenches needed strengthening and ‘revetting’. The trench sides crumbled easily after rain, so were built up (‘revetted’) with wood, sandbags or any other suitable material. The climate was warm and temperate in Nord-Pas-de-Calais, with significant rainfall. Even in the driest months there was a lot of rain. The ground in this area was soft chalk and one can imagine the sweat or rain-bathed faces of the many ex-miners covered in white chalk after hours on these fatigues.

On the night of 2/3 September B Company suffered 5 casualties from a trench mortar bomb. Total casualties now read as 3 killed and 14 wounded, although the real battle had not yet started. What passed through their minds at this time?

Rumours now started to circulate on the back of all of the current intense preparation activity. In fact, 15th Division received preliminary orders for Loos, on 27 August 1915.

New billets at Verquin, to the south of Béthune, were roomy but dirty. Instruction of extra bombers and machine gunners continued, as the troops practised the art of moving in and out of trenches quickly, while keeping safe from potential enemy fire.

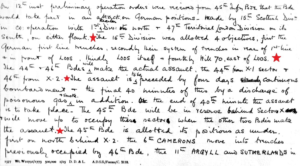

Five days later the battalion was back in the frontline trenches at Quality Street. They had transferred temporarily from 45 to 44 Brigade, but transfer slowed down as they had to use a narrow and incomplete communications trench. On 12 September 1915, preliminary orders were received for the upcoming action at Loos-en-Gohelle.

Attr: The National Archives – The National Archives' reference WO 95/1946/1

On the following two days, 13–14 September, they were under enemy attack from trench mortars and field guns.

Casualties were sustained on both days: 5 other ranks killed, 2 officers and 28 others wounded. Officers were named but other ranks were not.

The first two of Kitchener’s Volunteer armies of 100,000 (K1 and K2) were now fully prepared and ready for action. However, it is important to note that infantry troops had not been fitted with steel helmets at that time. Later, on 30 October 1915, British headquarters announced that, following the example of the French, some British troops had been equipped with light steel helmets as protection against shrapnel, and shell or bomb splinters. Only fifty helmets were allocated to each battalion. By early 1916, 250,000 had been made and all troops had Brodie helmets by the start of the Battle of Eloi, in April 1916.

A new element in British warfare was issued in these preliminary operation orders – the final 40 minutes of this bombardment would be accompanied by a discharge of poisonous gas and smoke. Today’s Porton Down facility did not open till April 1916, as the ‘Royal Engineers Experimental Station’ for testing chemical weapons.

Following the first large-scale use of chlorine gas, by the Germans, opposite Langemarck-Poelkapelle, north of Ypres, on 22 April 1915, the British and French complained that this was against international law. However, the British decided to develop their own gas-warfare capability. The chlorine gas used by the Germans in April and May 1915 came in liquid form, released from pressurised cylinders.

At that time, only the Castner Kellner company produced chlorine electrolytically from brine, which was suitable for liquefaction. The liquid chlorine was then used in colour-making and for the treatment of gold ore. In 1914, the company’s Runcorn plant produced about 5 tons of chlorine a week. As the only company in June 1915, with both the expertise and the necessary plant, Castner Kellner were instructed to increase production to 150 tons per week and install plant to fill pressurised cylinders with liquid chlorine. The first deliveries were made to the army on 26 July 1915. Castner Kellner received £18 for each ton of liquid gas produced.

The use of poisonous gas was successfully kept secret from the Germans. The gas was contained in 140lb cylinders and had to be in position at the front line by dawn on 21 September. Consignments of 500 cylinders arrived on each of the preceding three nights, delivered to Fosse 7, south of the Lens–Philosophe Road. These ‘special stores’ were transported by a party of twelve men, under an officer with an NCO, with two extra men in case of accidents. Over 1,000 men were used each night to transport the cylinders to the front trenches. The cylinders were handed over to men specially detailed to handle them on the day of attack.

This was a very successful operation and the team was congratulated and thanked by 15th Division Commander, General McCracken. His words when taking command in March 1915 had been, ‘Discipline, Discipline and Discipline’, and this was a great example of it in action.

As all of these aspects of battle preparation proceeded, the 13th Battalion of the Royal Scots moved to Noeux-les-Mines on 18 September, and remained there as they continued their training and final preparation.

The introduction of an expanded role for aircraft and the recently formed Royal Flying Corps (RFC) brought a new and valuable dimension to fighting battles and supporting troops in the trenches. On 23 September, No.2 and No.3 Wings of the RFC began the first concentrated interdiction campaign, aimed at disrupting German communications, in support of the Allied offensive at Loos. The RFC had a significant role operating over the area of 4th Corps that included Robert Dunsire and his colleagues. No. 2 Squadron was engaged in trench bombardment, artillery-flight counter-battery work and planes patrolling over Lens. 1 Corps, to the left of 4 Corps, enjoyed the same level and type of aerial support. Planes were also involved in long-distance tactical reconnaissance and patrolling behind enemy lines on behalf of First Army Headquarters. This included planes with wireless capability from No.16 Squadron, leading to a major advance in the use of flight in World War I.

At 22.30 on 24 September, the battalion left Noeux for an assembly position east-south-east of Mazingarbe. The strength of the battalion that set off for this position was 21 officers and 834 other ranks. Private Robert Anderson Dunsire (18274) of D Company of 13th Battalion of the Royal Scots was one of those 834 other ranks.

Sadly, 16 men were seriously wounded when ‘some careless individual’ dropped a box of Battye bombs (grenades) when marching through Mazingarbe. By the end of 1915, the Battye grenade was completely removed from service due to the number of injuries acquired by its use. The more reliable and sophisticatedly designed Mills bomb replaced it.

The Battle of Loos was imminent. This map from Lord Kitchener’s Papers indicates the planned positions of the 3 Brigades of IV Corps in readiness for action at Loos. In particular, 45 Brigade is in its designated position in Reserve near Mazingarbe. This included Robert Dunsire and his Battalion.

Attr: Copyright - The National Archives/Lord Kitchener’s Papers/ PRO 30/57/51