Mazingarbe was not occupied by the German army during World War I, and despite a lot of bombing, coal-mining never stopped. The town was to be a major transit point for troops entering or leaving Front line action. It provided a stopping off place for final preparations or being held in Reserve for a quick call-up; it also provided a resting off haven for exiting troops and hosted medical triage and treatment locations for the sick and the wounded. Sadly, death was also a frequent visitor as evidenced by the number of wartime graves in the town or its neighbouring communities.

Throughout all of this hubbub local people warmly welcomed the troops who stayed or passed through the town. On occasion, Scottish soldiers cut a dash in their kilts and prompted some passing female attention. Evidence of this can be found in old photographs like that of this group from the 1/14th Battalion of the First Division, London Scottish Regiment, as they lined up for souvenir photographs with local ladies.

Image Courtesy of Comité Historique Mazingarbe

The people of Mazingarbe still extend the hand of friendship to visitors who come to fill in the blanks in family history relating to World War 1. In doing so the Mazingarbois extend the hand of friendship with the same warmth and appreciation that welcomed our forefathers in World War 1. As a community, they will always remember the sacrifices of British soldiers or Les Anglais which was the common description of the time.

The front line a mile or so away had been established quickly by the invading German Armies. French troops formed the front line of defence till British troops and their supporting Armies of Indian and other ‘Empire’ troops arrived in Europe. They based their Field Hospital at Wattebled Chateau in Mazingarbe.

Image Courtesy of Comité Historique Mazingarbe

Villa Saint Arnould was built by a brewer, the brewery was behind the villa, and St Arnould is the patron saint of brewers. Mazingarbe was a major centre for much of the activity of 46 Field Ambulance after the end of the Battle of Loos. 46 Field Ambulance Station, manned at the time by William John Collins, was to receive the wounded and mortally injured Robert Dunsire VC. It was close enough to support advance dressing stations, such as the one at Philosophe.

Image Courtesy of Comité Historique Mazingarbe

The brewery (pictured above) behind Villa Arnould was used for baths by the 46th Ambulance Station, whereas the villa was used as HQ by Brigades and the 46th Ambulance Station.

British Infantry Troops were not billeted in grand chateaux, and many found themselves in houses like those in the image below. They would often seek refuge and rest in the basements of houses that had been damaged or partly destroyed by long range shelling.

Image Courtesy of Comité Historique Mazingarbe

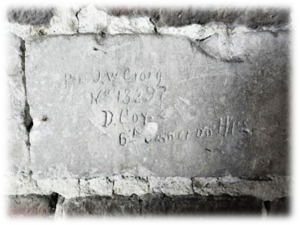

Ferme Dupuich, which has recently been transformed into the Mazingarbe Cultural Centre, was often a focal point for in transit Scottish troops. They left evidence behind in wall carvings that still exist today.

Individuals carved out their own piece of personal history. A particularly sad example of this is the carving by Private John W Craig, (13297) D Company, 6th Cameron Highlander. John Craig first travelled to France on 9 July 1915, within a few days of Robert Dunsire VC. He made it safely to Mazingarbe where he billeted at Ferme Dupuich with the remainder of the 6th Battalion of the Cameron Highlanders between 18-30 August 1915. In this short period John, like several other soldiers, left a carved souvenir of his stay which was uncovered during the building of the new Cultural Centre.

Less than one month later, in September 1915, The Battalion War Diary records that Private John Craig, Serial Number 13297, was wounded then died from rifle shot wounds while in a working party on 18 September. John was buried immediately at the Communal Cemetery at Noeux Les Mines.

Image Courtesy of Comité Historique Mazingarbe

The 9th Battalion of the Black Watch had two periods in billets in Mazingarbe prior to the start of the Battle of Loos. The first period was for a week from 17–18 August and from 1–3 September 1915. The Black Watch also left their visiting ticket at La Ferme Dupuich.

One century later, Ferme Dupuich has hosted several World War 1 exhibitions that I have enjoyed visiting. The life and soldiering of Robert Dunsire VC has been a regular feature of these exhibitions.

Image Courtesy of Comité Historique Mazingarbe

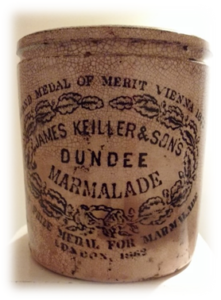

The marmalade jar from Keillers of Dundee, pictured below, was dug up in Mazingarbe in 1920. Perhaps, it had been sent in one of the many food parcels that arrived to the front to supplement a soldier’s daily army food rations. At the beginning of the First World War, Dundonian men typically joined the 1/4th (City of Dundee) Battalion, The Black Watch. This local territorial infantry unit was mostly resourced by men from the city and its immediate surrounding areas. The battalion came to be known as Dundee’s Own. Dundee’s Own fought its last battle as an independent unit at the Battle of Loos on 25 September 1915. Over two hundred men from Dundee’s Own were killed or injured and this high number meant that the battalion could not continue as an independent unit.

Keiller’s Marmalade Jar found in Mazingarbe

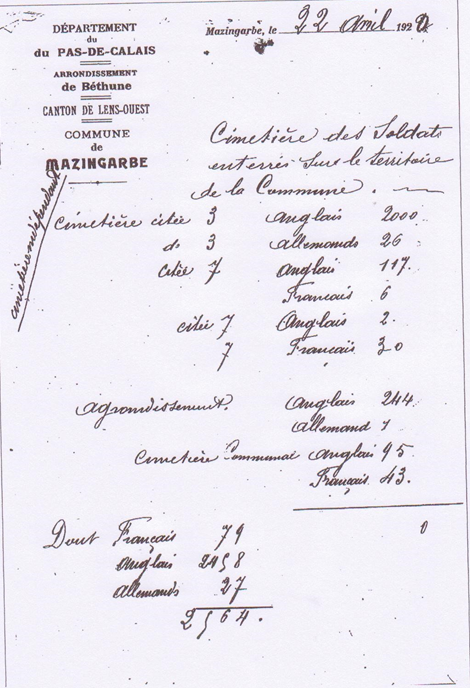

A permanent reminder is always present in the many war graves that can be found within the boundaries of the commune of Mazingarbe. The following document was prepared on 22 April 1920. The total number buried and remembered there is 2,564, of which 2,458 are British.

Image Courtesy of Comité Historique Mazingarbe

Sadly, the town of Mazingarbe had the burden of the loss of its own casualties. The World War I Monument to the Dead in Mazingarbe reveals a large number of military deaths. A further death toll was to result from Mazingarbe’s proximity to the front, just over a mile away – the town experienced heavy civilian casualties, with 77 civilian names from World War I remembered on the Mazingarbe War Memorial.

Image Courtesy of Comité Historique Mazingarbe

Mazingarbe was to play a reluctant role in another aspect of World War 1 deaths. Today these historical deaths are referred to as ‘Shot at Dawn’. It is always challenging to examine events of 100 years ago, especially when considering the actions of soldiers, in the kind of war that was never experienced again in the same manner, against enemy forces at such close proximity. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or ‘shell shock’, and the impact of mental health of participants in 1916 were barely recognised or treated. However, events happen and they should not be expunged but be debated and learned from in our modern-day assessment of our history.

Ninety years after their deaths, 306 of the 346 soldiers who were executed after court martial during World War I, were granted posthumous pardons from the British Ministry of Defence. These soldiers were executed during hostilities for breaches of military discipline that included desertion, cowardice, quitting their posts, striking a superior officer, sleeping at their post, and casting away their arms. The remaining group of forty soldiers was not granted a pardon because of the nature of their crimes, which included murder and mutiny. The 306 received no medal, are never mentioned in memorial services and their grieving families received no pension

Of the 200,000 men who were court martialled during World War I, 20,000 were found guilty of offences that carried the death penalty. Of those, 3,000 actually received the sentence, of which 346 were carried out. Four of these soldiers were only 17 years old. The pardon was for the Offence not the Execution.

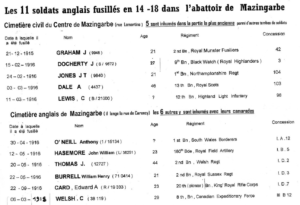

Eleven soldiers were shot against the wall of the abattoir in Mazingarbe. This document was provided by Gérard Delporte of the Comité Historique Mazingarbe.

Image Courtesy of Comité Historique Mazingarbe

A single plaque is mounted on the outside wall of the abattoir, and recognises the 2006 pardon of James Graham, the first soldier to be executed at Mazingarbe in December 1915.

One of the soldiers who was executed, but not pardoned, was a 45-year-old married man and former labourer, Arthur Dale, a Private and former colleague of Robert Dunsire VC in the 13th Battalion of the Royal Scots.

Dale had been found guilty of the murder of Lance Corporal James Sneddon. In the report of Royal Scots’ casualties, in The Musselburgh News of Friday, 10 March 1916, Lance Corporal Sneddon’s death is carefully categorised as ‘died’. It was reported in an identical manner in The Scotsman of 1 March 1916. I can find no newspaper report of the time that explained the circumstances of his death, but the following reveals the charge against Arthur Dale.

On 8 February 1916, while out on rest, Arthur Dale spent the day drinking in a local bar. His friend, Lance Corporal James Sneddon, came in and told him that he had drunk more than enough and should go back to his billet, which Dale did. Witnesses state that they saw Dale climb into his loft with his rifle and, a moment later, a shot rang out. Sneddon fell, mortally wounded. The witnesses and arresting police all stated that Dale was very drunk and incoherent. He was brought to trial on 20 February and condemned to death for murder.

The field general’s Court Martial Statement on behalf of the accused, given by Kinghorn born Captain Charles W. Yule, 13th Royal Scots, ‘Prisoner’s Friend’, states: ‘The evidence shows no premeditation or malice aforethought’. The deceased lance corporal himself said, ‘It was an accident’. Captain Yule produced Army Form B 122 – Dale’s Conduct Sheet – which had no entries apart from character ‘good’ and his declared age. The accused made no statement in mitigation. The warrant was signed by Major General F.W.N. McCracken, Commander of the 15 Division. Private Arthur Dale was executed at 06.35 on 3 March 1916, at Mazingarbe abattoir.

This publication in April 2015, by the Comité Historique Mazingarbe, documents the events and personal stories of what was happening to the Mazingarbois and to Mazingarbe throughout 1915. It also contains a short article about Robert Dunsire VC in the context of the Battle of Loos. In Issue 39, that appeared in June 2012, there was a very well-researched and excellent article about Robert Dunsire VC.

Comité Historique Mazingarbe deserve a very special mention for their work over very many years in documenting and exhibiting the history and stories about Mazingarbe. Throughout my working partnership, over the past eight years on my own journey of discovery with Robert Dunsire VC, my observation would be that, until 2015, Robert’s story was better known in France than at home.

Finally, it is to the people of Mazingarbe who turned to and looked upon our brave troops as the key to their freedom and survival. They played their own part and this was subsequently recognised in 1920.

The brave patriotic demeanour and attitude of the population of Mazingarbe throughout World War I was recognised by its receipt of the Croix de Guerre in 1920, whose citation states the following:

Bombardée par canons et par avions, a fait preuve d'une superbe vaillance et d'une patriotique fermeté malgré le nombre élevé de victimes dans sa population et des dommages qu'elle a subis.

[Bombarded by guns and planes, Mazingarbe Commune showed glorious bravery and patriotic determination despite suffering large number of casualties among the population and much damage to property.]

In the unfortunate circumstances of death in France during World War I Robert Anderson Dunsire VC could have a ‘no more caring’ final resting place than Mazingarbe.