Robert was now in France and firmly ensconced in D Company of 13th Battalion of the Royal Scots. As an Infantry Battalion, it had a typical formation.

- A battalion would have an establishment of 1,007, including 30 officers.

- Commanded by a lieutenant colonel.

- An infantry battalion was divided into headquarters, machine-gun section of 4 men, and 4 companies (often lettered A to D) of 227 officers and men.

- Companies contained 227 officers and men and were commanded by a major or captain.

- Each company had a company sergeant major, company quartermaster-sergeant and 8 sergeants.

- There were 4 drummers or pipers, 10 corporals and 188 privates.

- There might also be 3 drivers for transport and 6 batmen for officers.

- A company was divided into 4 platoons.

- Platoons would be numbered 1–4 in A Company, 5–8 in B Company, and so on.

- A platoon was divided into sections, with 16 sections in a company.

- A section contained 12 men led by an NCO.

In summary, one battalion consisted of 1 headquarters, 1 machine-gun section, 4 companies, 16 platoons, and 64 sections. It was only in February 1916 that separate machine-gun companies were formed.

On 2 September 1915, a definite proposal was made to the War Office for the formation of a single specialist machine-gun company per infantry brigade, by withdrawing the guns and gun teams from the battalions. These were replaced at battalion level by light Lewis machine guns and thus the firepower of each brigade increased substantially. The Machine-Gun Corps was not created by Royal Warrant till 14 October, followed by an army order on 22 October 1915. The pace of reorganisation depended largely on the rate of supply of the Lewis guns, but it was completed before the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Robert Dunsire had already trained and acted as a machine-gunner within the battalion.

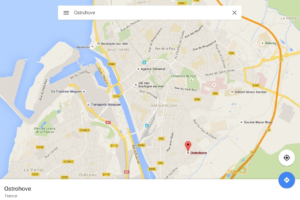

By 00.45 on 11 July 1915, the 13th Battalion arrived at their first resting place, having marched 3 miles to Ostrohove Rest Camp, south of Boulogne.

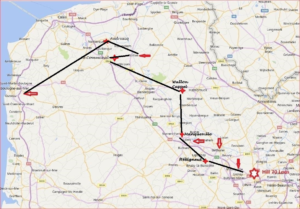

They were faced with a journey from the Coast to The Front of approximately 60 miles as the crow flies. In fact, the circuitous and safer route was double that distance. In 2016 I undertook the same journey on foot with a friend as part of my own commemoration of my grandfather’s World War 1 Service who was in the same Company and Battalion as Private Robert Dunsire. My journey, that I named ‘In Their Footsteps, Never in The Shoes’ followed the main stopping off points from Boulogne Sur Mer to Loos-en-Gohelle. I was not burdened by a heavy kit bag, new boots, rifle etc.

They were soon on the move again leaving Ostrohove at 16.20, heading for a train at Pont-de-Briques. The train journey from Pont-de-Briques to Watten was via Audruicq, and employed the established French rail network.

From Watten Station they marched 5 miles west to Bayenghem-lès-Éperlecques. Robert’s company then marched a further 1.5 miles to their camp at Le Communal, their base till 15 July. There, they spent their days route marching, practising bayonet fighting and bomb-throwing.

The battalion moved on from Le Communal on 17 July, with a 19-mile route march to billets at Wallon Cappel. This long march across cobblestones tested the soldiers’ new boots that had been issued before they left England, as they continued their progression to the battle front. The War Diary records, ‘there were many stragglers – very bad exhibition’. A judicious comment in the margin notes, ‘When shall we learn – Experience!’

That night they were not far from the action over the trenches at the not-too-distant Belgian border towards Ploegstert. Constant flashes from German shells were clearly seen bursting over the trenches, accompanied by the never-ending rattle of gunfire.

Despite this, Robert and his colleagues were on the march the next day with a 15-mile hike to Manqueville, 1 mile to the north-west of the centre of Lillers. It was noted that the men marched much better. After billeting there overnight, they were on their feet again for another march to Hesigneul, south of Béthune. This was a ‘shorter march’ of 12 miles. Only two men dropped out.

They bivouacked in a field and conditions were ‘very dirty and unsatisfactory’. Not the best situation after 3 days and 46 miles of fully kitted marching in July. It was more like an exercise in acclimitisation for what was yet to come.

Many poems were written about the experiences of soldiers on the front line and the impact on their lives and senses. Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967) wrote many fine pieces and the poem.

Sassoon’s poem, ‘Trench Duty’, illustrates what must have passed through the minds of many soldiers as they took up position in the trenches. The poem can be read at https://poets.org/poem/trench-duty

On the evening of 19 July they headed for the deserted garden village of Maroc, near Grenay, in the heart of the principal mining area of France, with familiar pit tops and pit bings, or ‘coal slags’. Typically, they used abandoned houses as billets or be ‘house guests’! For a miner who had left Denbeath some six months before, it was a familiar environment for Robert, as Denbeath had also been constructed as a garden village. Robert was only 0.75 miles or 1 kilometre from the front and the well-established German lines – a new reality for all of the 13th Battalion of the Royal Scots.

The image below shows a typical Map of the Trenches. This is the area at Grenay and Maroc. German trenches are shown in red and British trenches in blue. No Man’s-Land was not wide, often between 200 to 400 yards.

Within a few days, companies formed working parties assigned to the Royal Engineers, to dig communications trenches that led to the very front of the British lines. These trenches were an important element of the trench infrastrucure that was used to move fresh troops to the front to relieve another battalion or regiment of the 15 Division. Soldiers had to squeeze past each other during this process. Carrying parties took supplies of water, food, ammunition, bombs and trench stores along the 400–500-yard-long communications trenches to the front line. The communication trench was also used to transport wounded men to a Casualty Clearing Station at the rear of the trench lines – it was a main artery. They had their first experience of directed German shelling on 25 July.

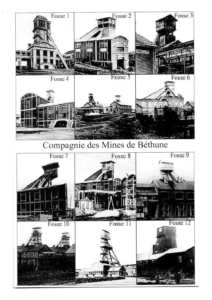

The battalion was relieved overnight on 25/26 July by the 6th Battalion of the Gordon Highlanders. They retired to billets at Labeuvrière, which was well back from the front and 2 miles west of Béthune. The coal company of Béthune owned 12 mines in an area that produced 75 per cent of France’s coal before the start of World War I. Robert was still in a mining area, but with new challenges for the weeks ahead.

This was an opportunity for some officers and NCOs to be allocated for frontline experience with other regiments, battle-hardening experience was important preparation. The ‘ranks’, as they were referred to, participated in sessions to hone their trench warfare skills in simulated battles in customised training areas. There was little opportunity for rest time, although no doubt Robert would have taken the opportunity to join group musical sessions. Other War Diaries note that there were church services at this time but the 13th’s Diary does not. Individual battalion diarists had their own style and content notions.

One week later, on 2 August, the 13th Battalion relieved the 6th Battalion of the London Regiment at billets at Philosophe, near Mazingarbe, as part of 15th Division, replacing 47th Division at the front line.

However, action at The Front was imminent.