The Battle’s O’er for Robert and the Battalion

On 28 September the battalion welcomed a new draft of 68 soldiers. They had probably come straight from training in Britain as was the norm at this time in strengthening the First Army after major engagements.

One day later, Robert and his exhausted colleagues marched the short distance to bivouacs at Labuissière. After just 3 hours’ rest, they marched on the short distance to billets in Bruay-la-Buissière. The battalion Diary notes with joy that, ‘the natives seemed quite pleased to have us, their first experience of British troops’.

Though the battle rolled on till mid-October, there are many end dates set out in historical records. I have chosen the date of 16 October, as documented in the National Records of Scotland, as Loos is often referred to as ‘The Scottish Battle’ because of the estimated 30,000 Scots and more than 30 Scottish battalions who fought there over this brief three-week battle.

As far as the 15th Division and 13th Battalion were concerned, the battle was over at the end of September. In their book, The Fifteenth (Scottish) Division 1914–1919 (1926), Lt Col J. Stewart DSO and John Buchan state:

Pages might be written concerning actions of individuals on those two memorable days. The best and shortest commentary upon them all is contained in a certain official report of the operations: ‘When all did so well it would be invidious to make distinctions. It was difficult to say which had the best right to be proudest, the officers of their men or men of their officers’.

Early on 1 October the battalion marched back to Labuissière, where they were addressed and complimented on their efforts during their time in Loos by Sir Henry Rawlinson, Commander of IV Corps – 45 Brigade was part of this corps.

Robert bivouacked in the splendid surroundings of the Chateau at Labuissière, pictured above in 1908, for the next two nights before marching to Allouagne to billet with the rest of 45 Brigade, who spent the next week there as they rested, cleaned up and received new drafts to bring the battalion back up to strength.

They now had 26 officers and 1,061 other ranks, testimony to the number of new volunteer recruits, as there was still no conscription at home. Lord Derby’s scheme was only introduced to bring fresh impetus to volunteer recruitment when he became Director General of Recruiting, on 11 October 1915. Conscription only arrived when the Military Act was passed in January 1916. Faced with appalling casualty figures and a decline in voluntary recruiting, the British Government introduced the first Military Service Act in January 1916 (Gazette, Issue 29454), rendering all single men and childless widowers between the ages of 18 and 41 eligible for conscription.

This was all ahead. In the meantime, the battalion was put on notice that it had to be ready to move at one hour’s notice. On the 12 October they marched to Houchin – 3 miles from Béthune – to billet there. The following day they were put on notice to be ready to move at 30 minutes’ notice. Within 24 hours the battalion was on the move and soon billeted in familiar territory at Philosophe from 15 to early 19 October, when they were sent into brigade support in the trenches on the Vermelles–Hulluch road. They remained there for another three days before returning to the firing line when they relieved the 7th Royal Scots Fusiliers on 22 October. They remained there for four days before being relieved by the 10th Gordon Highlanders.

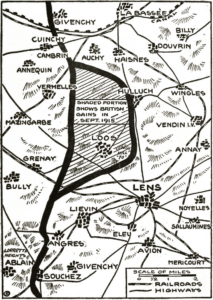

The following map illustrates the ground that was finally secured during The Battle of Loos and was the area in which Robert and the 13th would operate on the future.

Elsewhere it was noted that the weather had been fine up to 10 October, but it then broke to bring torrents of rain, and the ground quickly became a quagmire. The trench network was poor in this area and had suffered constant attacks during the early phases of the Battle of Loos, when limited progress, if any, was made in this area. The German forces had a clear view of activity during the day, so the movement of troops above ground in daylight was restricted. Some of the communications trenches back to Vermelles stretched to a distance of 2.5 miles (4 kms). The constant rain meant little maintenance or draining of these major routes was possible.

The relief by the Gordons took 13 hours as the relief path was down one single trench. They then had to march to Noeux-les-Mines to go into divisional reserve between 26 and 31 October. King George V inspected detachments of the 15th Division at Labuissière on 28 October. There is no diary entry for the involvement of Robert or any of his battalion colleagues.

The 13th took over the firing lines on the south-west edge of the Quarries on 1 November. The Diary reports that it poured with rain and that trenches and parapets were falling in everywhere. The complaints continued about the rain. Reports explained that 70 per cent of rifles were choked with mud and out of action. The enemy shelled their support and communications trenches; ‘chiefly for our artillery work on their trenches’.

A ‘favourite’ World War I song was titled ‘Raining and Grousing’ (listen to https://us.audionetwork.com/browse/m/track/raining-and-grousing_82414). This version was recorded on an old microphone to give the effect of age.

At this time, the first issue of steel helmets was made on a scale of 50 per infantry unit. Initially these helmets were used as washing basins and it was some time before the battalion was fully kitted and helmets were used for their designed purpose.

Intermittent shelling and constant rain continued. All communications with brigade HQ and artillery were down for 36 hours before yet another relief moved back to brigade reserve at Noyelles. Knee-deep in mud, rain and shelling, exhaustion summed up their day of relief. But before they moved back, they did good work digging ‘saps’ – short trenches dug towards the enemy trenches, enabling soldiers to move forward without exposure to fire – and straightening out the firing line. Several saps would be dug along a section of front line.

It was very cold in Noyelles, where working parties of 350 had little opportunity to rest or clean themselves up. Given all what had gone before it is no surprise that Private Robert Dunsire soon appealed for more men to come forward to help with trench-digging. It was tough work in brutal conditions.

The battalion turned again to frontline activity when they moved back a sector south-west of the Quarries, where they were met by active, day-long enemy artillery. Trench and sap work continued and soldiers were even involved in burials of 12th Division casualties. This routine of digging saps pushed on at 50 yards per day as the trenches continued to be bombarded day and night.

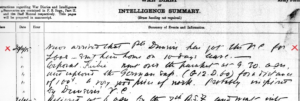

On 10 November, Robert and his colleagues returned to brigade reserve in Philosophe and Vermelles. They caught enemy fire, but no weather respite for the next 48 hours, and were put on standby at 13.30 on 12 November, in case they had to support the 7th Royal Scots Fusiliers, who were under heavy shelling at the Hairpin Craters, immediately west of the Quarries. With no need to go forward, the next day the battalion returned to divisional reserve at Verquin, where they remained in the rain for another six nights. On 19 November. they returned to Vermelles–Hulluch Road trenches, but news was breaking about Private Robert Anderson Dunsire. His world was about to change quite dramatically as this low-key entry in the battalion diary appeared.

Attr: The National Archives – The National Archives' reference WO 95/1946/1