It was not only local men who were prepared to make contributions to the War effort. Some women chose to go to the front to fulfil volunteer roles; for example, in the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (SWH). Women made an enormous contribution at home as they backfilled a variety of jobs that had been left by male volunteers, who had responded to Kitchener’s clarion call to come forward. They also worked in jobs that supported the men at the front by working in manufacturing, including in ammunition factories, and agriculture.

The Scottish Women’s Hospital (SWH) movement was founded in 1914, soon after the outbreak of war, in response to the rejection of medical women joining the Royal Army Medical Corps. Elsie Inglis from Edinburgh was its founder.

The British Red Cross was hampered by War Office regulations regarding the work of women, and so was unable to help Elsie Inglis and her new movement, thus the SWH had to act independently. However, this did not stop action by women from Robert’s local area.

The first French unit of the SWH arrived in France in December 1914, and formed a base hospital at Royaumont Abbey, 12 miles from Chantilly, on the outskirts of Paris. The first of several Serbian units followed soon after. They provided nursing services, doctors, ambulance drivers, cooks and orderlies.

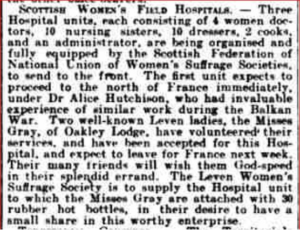

An early example was that set by the Misses Gray of Oakley Lodge, Leven whose decision to travel was announced in the Leven Advertiser & Wemyss Gazette of 12 November 1914.

Attr: Newspaper image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

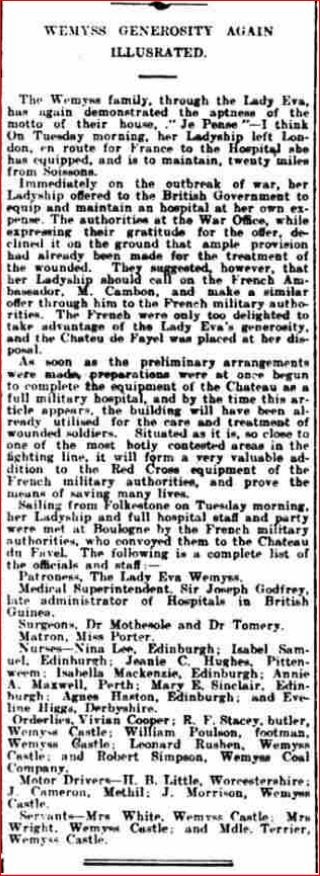

An article in the Dundee Courier of 20 November 1914 explained that Lady Eva Wemyss had approached the British War Office with an offer to equip and take a field hospital of 35 beds to France. At that time, it was expected that the hospital would be at Nantes on the banks of the River Loire.

It was the 11 February 1915 edition of the Leven Advertiser & Wemyss Gazette finally reported that Lady Eva and her entourage were heading for Chateau du Fayel, west of Soissons and north of today’s Charles de Gaulle Airport. The agreement to create the field hospital was made with the French Ambassador in London rather than the British War Office.

Her complement of staff included Nurse Hughes. According to The British Journal of Nursing, she had been the district nurse in Pittenweem, in the East Neuk of Fife, for two years, and had also worked at Wemyss Hospital.

Lady Eva donated a sum of around £10,000 (equivalent to £1 million today) for the building of the hospital, but many of the fixtures, fittings and equipment were provided by donations from well-known local people and businesses.

Attr: Newspaper image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

In December 1914, another name that was to become familiar to twenty-first-century Scotland left for Serbia – Sister Louisa Jordan. Louisa Jordan was born in Glasgow. Her qualification as a Queen’s Nurse (a district nurse) was announced in The Dundee Evening Telegraph and Post on 31 October 1913. Louisa then moved to Fife, living and working in Buckhaven as a district nurse for just over a year. She signed up with the SWH as a nurse on 1 December 1914, and joined the 1st Serbian Unit, under the command of Dr Eleanor Soltua. They headed for Salonika (now Thessaloniki) in Greece. On arrival, the unit were sent up to Kraguievac, a city 100 miles south of Belgrade. Although the fighting at that time was minimal, there was still a massive amount of work to be done, and Serbia was very short of medical facilities.

However, by February 1915, typhus had broken out. Typhus is a cold-weather disease, spread by body lice, and thrives in overcrowded, dirty conditions. Kraguievac met all the requirements for this killer. By the middle of February, a typhus ward was up and running, with Louisa, who had some experience having worked in Shotts Fever Hospital, in charge

Also working there was Dr Elizabeth Ross from Tain, in the north of Scotland. She was not a member of the SWH and had travelled to Serbia alone when war broke out, and been assigned the typhus wards of a military hospital. Louisa and Elizabeth knew each other well. When Elizabeth became ill with typhus, she helped nurse her, but sadly Elizabeth died on 14 February 1915. She wrote: ‘We really felt we had lost one of our own.’ Sadly, this would be one of last entries in her diary as a few days later Louisa Jordan also died of typhus.

Louisa Jordan is remembered on Buckhaven and Methil War Memorial as the sole local casualty of Scottish Women’s Hospitals.